Day of the Dead

The Day of the Dead, Myth, Magic and Mysticism

by Monica Sauza

The ancestral mysticism and respect for the souls of the departed, flows deeply embedded in the bloodstream of a nation; they return home to coexist with living relatives and feed from the essence of the food offered in the altars. This is the time for the most mystical gathering between the living and the dead.

A memory of a time when after a four year journey through Mictlán and its 9 dimensions, after gifts had been presented to the Aztec deities Mictecacíhuatl, the Lady of the Dead, andMictlantecuhtli, the Lord of the Underworld, the dead were shown where their souls would peacefully rest until called to return to their old home. The ceremony offering crops to these deities at the end of the farming cycle (August), became a ritual.

A ritual that has lasted to our times, fused into one by the encounter of two worlds and cultures. Around June, the Aztecs celebrated the feast to the “small dead” or children, and in August, the “big dead” or adults, which lasted up to two months. Upon the imposition of a new religion, its calendar and beliefs, these feasts became the All Saints’ Day (or children) on November 1st and the All Soul’s Day on November 2nd(adults). Despite the catholic influence, the tradition of this Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO, 2003) still holds many elements, mysticism and myths of the original ceremonies.

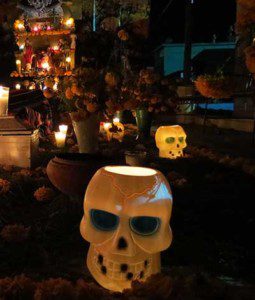

The pre-Hispanic cult to the dead is still preserved in a wide number of places in Mexico, not just as a cult but mainly to honor ancestors. In some places bonfires are lit, in others, the bright orange zempasúchitl flowers (marigolds), or flower of the dead, are placed pointing the way to the doorsteps of relatives’ homes who expect the arrival of the spirits of those who went before them. Inside the house, incense and candles are lit; the table is set for dead relatives who will visit for a short while.

In contrast to our current vision of death, ancient Mexican cultures believed that this was just another step in the existence of the soul, a part of the cycle of creation. The Mazahuas of the State of Mexico and Michoacán believed that after living, the dead arrive to another world similar to the earthly plane they left behind.

In contrast to our current vision of death, ancient Mexican cultures believed that this was just another step in the existence of the soul, a part of the cycle of creation. The Mazahuas of the State of Mexico and Michoacán believed that after living, the dead arrive to another world similar to the earthly plane they left behind.

Before midnight, children, women and men respectfully head to the cemetery with offerings of zempasúchitlflowers, food, drinks, bread, tortillas, candy and fruit which the dead relative liked so much, and carefully and reverentially set up altars upon their graves; candles are lit one by one in the cemetery, prayers and sweetPurepecha songs fill the air, while a discreet bell is heard all night calling the souls of departed loved ones to this great ceremony.

In Janitzio, an island in the lake of Pátzcuaro, State of Michoacán it is the night ofAnimecha Kejtzitakua, night of the dead, when the shadows of princess Mintzita and prince Itzihuapa rise. Despite their great love, Mintzita and Itzihuapa were not able to marry because Spanish conquistadors had captured her father. For her father’s rescue, Mintzita offered in exchange a superb treasure found under water in the lake. When Itzihuapa was ready to lift out the treasure, he was trapped by twenty shadows of the guardians who had originally hidden the treasure. Itzihuapa became the twenty-first guardian of the treasure.

On this night, the guardians rise and climb the steep slope of the island. And in the cemetery the princess and prince reunite and receive offerings from the living while whispering their love to each other and give their blessings to the living. Being part of this ceremony is a sacred duty to the dead and an honor for those who participate. On November 1st the very movingKejtzitakua Zapicheri ceremony, or Vigil for the Little Angels, takes place at the churchyard. Mothers, sisters and brothers create beautiful flower ornaments, placing candy skulls and wooden toys on the graves of children; gifts that were not given in life will decorate their altars.

The rich tapestry of smells, colors, songs and this ancestral tradition is wonderfully represented in Tzintzuntzán (Place of the Hummingbirds) also in the State of Michoacán.

Tzintzuntzán is the place from where the god Huitzilopochtli marched out to establish the great Aztec empire in the Valley of Mexico. Just as other places in Pátzcuaro, this quaint village in the riverbank of Lake Pátzcuaro, three tiered altars are placed representing the universe: first, Auándaro, the heaven where gods lived; the second, Echerendo or echerio, earth, where man lived; and the third, K’umienchékuaro, the underworld. The Purepecha people also believed that man did not die, the journey continued to another place.

The altars never lose its essence, whether in the cemeteries or in homes. According to tradition these must have seven tiers, almost two meters high, and be prepared days before the celebration, always filled with colorful papel picado or chiseled paper with floral and skeletons designs, zempasúchitl flowers, candles, photographs and personal belongings of the departed, salt, water; food including fruits, mole, tamales and other delicacies; beer, mezcal, tequila or other alcoholic drinks; atole, champurrado and chocolate, candy skulls with the names of the departed.

In Mexico, the celebration of the Day of the Dead is a mixture of mystical devotion, bringing together religion and paganism, fear and mockery. Songs are made to the death, ridiculed in cartoons and skulls, and eaten in candy or bread, making of it a very significant and particular celebration. The Catrina makes a very good example of this representation, which became the official symbol of Death in Mexico. The image of this skeleton lady, Calavera Garbancera was created before the Mexican Revolution by cartoonist and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada, and later renamed as Catrina by painter Diego Rivera and ridiculed in his famous muralSueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park), with the Catrina as the central figure, Diego as a boy and his wife, Frida Kahlo at her side. His intention was to criticize the wealthy and political society of the time, reminding them that, in the end, we all die. The Catrina has since been crafted using many different materials, designs and paintings, represented in multiple forms, shapes, colors, attires; sometimes happy, others, flirtatious and provocative, but always defined in accordance with the region.

In Mexico, the celebration of the Day of the Dead is a mixture of mystical devotion, bringing together religion and paganism, fear and mockery. Songs are made to the death, ridiculed in cartoons and skulls, and eaten in candy or bread, making of it a very significant and particular celebration. The Catrina makes a very good example of this representation, which became the official symbol of Death in Mexico. The image of this skeleton lady, Calavera Garbancera was created before the Mexican Revolution by cartoonist and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada, and later renamed as Catrina by painter Diego Rivera and ridiculed in his famous muralSueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park), with the Catrina as the central figure, Diego as a boy and his wife, Frida Kahlo at her side. His intention was to criticize the wealthy and political society of the time, reminding them that, in the end, we all die. The Catrina has since been crafted using many different materials, designs and paintings, represented in multiple forms, shapes, colors, attires; sometimes happy, others, flirtatious and provocative, but always defined in accordance with the region.

In a simple, but ethereal way, this mystical pre-Hispanic cult to death warmly welcomes the souls of the dearly departed that wander upon the earth to share the sincere offerings of the living.

Día de los Muertos: Mito, Magia y Misticismo

por Monica Sauza

El misticismo y el respeto ancestrales hacia las almas de los difuntos, fluyen profundamente arraigados en el torrente sanguíneo de una nación; ellas regresan a casa para convivir con los familiares vivos y alimentarse de la esencia de los alimentos ofrecidos en los altares. Esta es la época de la reunión más mística entre los vivos y los muertos. Un recuerdo de aquel tiempo cuando, después de un viaje de cuatro años a través de Mictlán y de sus 9 dimensiones, después de presentar regalos a las deidades aztecas Mictecacíhuatl, la Dama de la Muerte, y Mictlantecuhtli, el Señor del Inframundo, a los muertos se les mostraba el sitio donde

sus almas descansarían en paz hasta retornar a su antiguo hogar.

La ceremonia de ofrendas de la cosecha a estas deidades al final del ciclo agrícola (Agosto), se convirtió en un ritual. Un ritual que ha perdurado hasta nuestros días, fusionado en uno solo por el encuentro de dos mundos y culturas. Alrededor del mes de Junio, los aztecas celebraban el mes de los “muertos pequeños” o niños, y en Agosto a los “muertos grandes” o adultos, la cual duraba hasta dos meses. Al imponerse una nueva religión con su calendario y creencias, estas fiestas se convirtieron en el Día de Todos los Santos (o niños) el 1º de Noviembre y el Día de los Muertos (adultos) el 2 de Noviembre.

A pesar de la influencia católica, la tradición de este Patrimonio Cultural Intangible (UNESCO, 2003) aún mantiene muchos elementos, misticismo y mitos de las ceremonias originales.

El culto prehispánico a los muertos aún se conserva en muchos sitios en México, no sólo como culto sino principalmente para honrar a los ancestros. En algunos sitios se encienden fogatas, en otros, las flores de zempasúchitl, o flor de muerto, con su llamativo color anaranjado, se colocan señalando el camino hacia los hogares de los familiares que esperan la llegada de los espíritus de aquellos que se les adelantaron.

Dentro del hogar, se encienden el incienso y las velas; la mesa se prepara para los familiares fallecidos que harán una breve visita. En contraste con nuestra visión actual sobre la muerte, las antiguas culturas mexicanas creían que esta sólo era una etapa más en la existencia del alma, una parte del ciclo de la creación. Los mazahuas del estado de México y Michoacán, creían que después de la vida, los muertos llegan a otro lugar similar al plano terrenal que dejaron atrás.

Antes de la media noche, los niños, mujeres y hombres respetuosamente se dirigen al cementerio con ofrendas de flores de zempasúchitl, alimentos, pan, tortillas, bebidas, dulces y frutas que a los familiares difuntos gustaban tanto, y cuidadosa y reverencialmente colocan los altares sobre sus tumbas.

En el cementerio se encienden una por una las velas, las oraciones y dulces cantos purépechas llenan el aire, en tanto se escucha una discreta campana sonar toda la noche llamando a las almas de los difuntos a esta gran ceremonia. En Janitzio, una isla en el lago de Pátzcuaro, estado de Michoacán es la noche de Animecha Kejtzitakua, noche de los muertos, cuando las sombras de la princesa Mintzita y del príncipe Itzihuapa ascienden.

A pesar de su gran amor, a Mintzita e Itzihuapa no les fue posible casarse debido a que los conquistadores españoles habían capturado al padre de la princesa. Para rescatar a su padre, Mintzita ofreció a cambio un tesoro magnifico que se encontraba debajo de las aguas del lago. Cuando Itzihuapa estaba listo para sacar el tesoro, se vio atrapado por veinte sombras de los guardianes que originalmente habían ocultado el tesoro. Itzihuapa se convirtió en el vigesimoprimer guardián del tesoro. Esta noche, los guardianes se despiertan y suben por la empinada pendiente de la isla. Y en el cementerio la princesa y el príncipe vuelven a reunirse, recibiendo las ofrendas de los vivos en tanto susurran su amor y bendicen a los vivos. Ser parte de esta ceremonia es un deber sagrado hacia los difuntos y es un honor para quienes participan.

A pesar de su gran amor, a Mintzita e Itzihuapa no les fue posible casarse debido a que los conquistadores españoles habían capturado al padre de la princesa. Para rescatar a su padre, Mintzita ofreció a cambio un tesoro magnifico que se encontraba debajo de las aguas del lago. Cuando Itzihuapa estaba listo para sacar el tesoro, se vio atrapado por veinte sombras de los guardianes que originalmente habían ocultado el tesoro. Itzihuapa se convirtió en el vigesimoprimer guardián del tesoro. Esta noche, los guardianes se despiertan y suben por la empinada pendiente de la isla. Y en el cementerio la princesa y el príncipe vuelven a reunirse, recibiendo las ofrendas de los vivos en tanto susurran su amor y bendicen a los vivos. Ser parte de esta ceremonia es un deber sagrado hacia los difuntos y es un honor para quienes participan.

El 1º de Noviembre la conmovedora celebración Kejtzitakua Zapicheri o Velación de los Angelitos, se celebra en el atrio de la iglesia. Las madres, hermanas y hermanos crean bellos adornos de flores, colocan calaveras de dulce y juguetes de madera sobre las tumbas de los niños; regalos que no les fueron entregados en vida decoraran sus altares.

La rica amalgama de olores, colores, canciones y esta tradición ancestral es representada de una manera espectacular en Tzintzuntzán (lugar de los colibríes), también en el estado de Michoacán.

Tzintzuntzán es el lugar del que el dios Huitzilopochtli partió para establecer el gran imperio azteca en el Valle de México. Al igual que en otros lugares en Pátzcuaro, este pintoresco poblado en la ribera del Lago de Pátzcuaro, se colocan altares de tres niveles representando el universo: primero, Auándaro, el firmamento donde habitan los dioses; el segundo,Echerendo o echerio, la tierra, donde habitaba el hombre; y el tercero, K’umienchékuaro, el inframundo. El pueblo purépecha también creía que el hombre no moría, la travesía continuaba hacia otro lugar.

Los altares nunca pierden su esencia, ya sea en los cementerios o en los hogares. De acuerdo a la tradición, estos deben ser de siete niveles, casi dos metros de alto, y se preparan días antes de la celebración, siempre llenos de colorido papel picado, flores de zempasúchitl, velas, fotografías y cosas personales de los difuntos, sal, agua; alimentos, incluyendo frutas, mole, tamales y otras exquisiteces; cerveza, mezcal, tequila u otras bebidas alcohólicas; atole, champurrado y chocolate, calaveras de azúcar con los nombres de los difuntos.

En México, la celebración del Día de los Muertos es una mezcla de devoción mística que une a la religión y al paganismo, el miedo

y la burla. Se hacen canciones a la muerte, ridiculizada en caricaturas y calaveras, y se come en dulce o en pan, haciendo de esta una celebración muy significativa y particular.

La Catrina es buen ejemplo de este simbolismo. La imagen de esta esquelética dama, la Calavera Garbancera fue creada antes de la Revolución mexicana por el caricaturista y litógrafo José Guadalupe Posada, y a la que posteriormente Diego Rivera la llamara Catrina, ridiculizada en su famoso mural Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda con la Catrina como la figura central, Diego como un niño y su esposa, Frida Kahlo, a un lado de la Catrina. Su intención era criticar a los ricos y políticos de la época, recordándoles que, al final, todos morimos. Desde entonces, la Catrina es concebida haciendo uso de diferentes materiales, diseños, pinturas; representada en múltiples formas, modelos, colores, vestimentas; en ocasiones feliz y, en otras, coqueta y provocativa, pero siempre definida de acuerdo a la región.

En una forma sencilla, pero etérea, este místico culto prehispánico a la muerte da la cálida bienvenida a los queridos difuntos que deambulan sobre la tierra para compartir las sinceras ofrendas de los vivos.

- Day of the Dead Cozumel - November 8, 2024

- Cozumel History Mexican Revolution Monica Sauza - November 8, 2024

- Day of the Dead - November 1, 2024