Day of the Dead Cozumel Monica Sauza

Day of the Dead Cozumel Monica Sauza

October celebrations and the beginnings of the Day of the Dead

by Monica Sauza

In Mexico, no matter where you look and what month it is, there are always events and celebrations taking place throughout the country. Every year, from the first Friday in October until the first Monday in November, Guadalajara’s month-long festival takes place around a specific theme; this year’s motto is “47 years of tradition”.

The popular event in the state of Jalisco has entertainers, dances, films, ballet, paintworks, the traditional palenque, concerts and cockfights, livestock fair, sport activities, also handmade and industrial products are sold.

From October 3 to the 21st. in Guanajuato, birthplace of the Mexican War of Independence and considered World Heritage Site by UNESCO, one of the four most important artistic and cultural events of its type in the world takes place: the International Cervantine Festival.

As member of the European Festivals Association and marking its 40th edition with more than 3000 performers this year, this colonial city, its plazas, parks, theaters and streets are filled with the most relevant expressions in opera, theater, dance, visual arts, music, film and literature from the five continents. One can join the bustle of the traditional “callejoneadas” while between laughs and lively tunes played by the estudiantinas https://youtu.be/Kvz6BJ0r0-U?si=brJG_IFA9PPStvhQ, you walk along cobblestone streets discovering many secrets of Guanajuato’s streets, such as the famous “Alley of the Kiss”, narrow enough that it allowed lovers to kiss each other from their balconies.

This Festival has its roots in the performance of short plays with a tint of comedy, the Interludes, written by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, the renowned author of a famous book which begins with the words “In a village of La Mancha, the name of which I have no desire to call to mind, there lived not long since one of those gentlemen…”, the immortal Don Quixote. Cervantes is considered one of the world’s leading representatives of the Spanish language sharing with William Shakespeare an honored place in universal literature. Cervantes and Shakespeare never met but, interestingly enough, both died on the same year.

In Mexico, celebrations reflect a rich pre-Hispanic heritage, culture and diversity as well as the religious influence of Spanish colonialism. Such is the case in Yucatan with the feast to the Exalted Christ from October 18 to the 28th, when the most revered image is carried in procession by pilgrims of Sitilpech all the way to Izamal, where candles and flowers are placed at the foot of the image.

The second Monday in October, in the quaint village of Santa Maria del Tule in Oaxaca a celebration takes place around one of the oldest trees in the world: the colossal 41 mts high, 2000 plus old Tule Tree (Montezuma Cypress) or Ahuehuete (“old man of the water” in ancient Nahuatl) http://www.mexicomaxico.org/Tule/Galeria/TuleH.jpg Two Mixtec legends speak about the origins of the Tule Tree (“tree of illumination”); one tells us that the tree was planted around 1400 years ago by Ehécatl, god of the wind; the second one speaks about mighty king Condoy, builder of the city of Mitla, who sat down to rest and as he stuck his cane into the ground, the plant sprung forth.

During colonial times, in order to preserve religious values, the indigenous communities adapted the new religion into their ancestral beliefs which brought forth very particular fusions. One of these adaptations can be seen on the October 4 celebration to Saint Francis of Assisi in Cuetzalan, Puebla, where the town is decked-out with many spectacular dances, and the Dance of the Quetzales is the most representative. This ritual dance from pre-Hispanic times was devoted to the sun and the dancers still wear large circular and colorful headdresses, the cuetzaltique, emulating the colors of the quetzal bird.

During colonial times, in order to preserve religious values, the indigenous communities adapted the new religion into their ancestral beliefs which brought forth very particular fusions. One of these adaptations can be seen on the October 4 celebration to Saint Francis of Assisi in Cuetzalan, Puebla, where the town is decked-out with many spectacular dances, and the Dance of the Quetzales is the most representative. This ritual dance from pre-Hispanic times was devoted to the sun and the dancers still wear large circular and colorful headdresses, the cuetzaltique, emulating the colors of the quetzal bird.

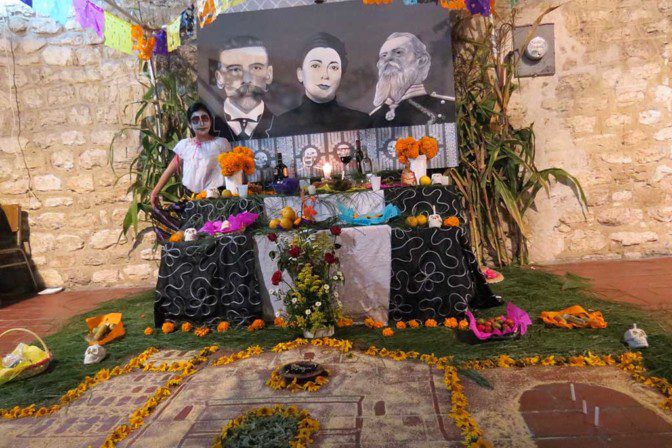

The most colorful, magical and historical representation of the Mexican culture in October-November is expressed in the millenary tradition of the Day of the Dead. Despite of the best efforts of Franciscan missionaries who modified the original date of the celebration, which in turn derives from Celt traditions, ancient rituals to the dead survived strongly rooted. These rituals were also closely associated to the end of the farming cycle. Pre-Hispanic cultures were not afraid of death as they believed that death and life were part of an unending cycle that must be accepted as a natural succession of the universe.

Even though the religion brought by the Spaniards in the XV century implanted fear to death, the vision of the ancients towards death was so strong that it prevailed. In all cultures in ancient Mexico, death had a very important place; a place where all immortal souls arrived. The Nahua and Mexica peoples called this place Mictlán. However, not all dead were the same. Many became gods; warriors became birds with wondrous plumage, whose mission was to escort the sun, Tonatiuh, every day and women who died giving birth arrived to Omeyocan, the paradise of the Sun. However, the trip to Mictlán was not easy as the dead must cross a very deep river, fight wild beasts, etc. Therefore people were buried with an obsidian knife, enough food and drink for the trip and a dog to tag along; and if this was an important leader, servants were also buried with the leader. The Maya considered the soul as indestructible, invisible and eternal, and death was a cyclical continuity between life and death. The dead traveled to the underworld, Xibalbá, and were buried with corn, food, drink, personal belongings and also a dog.

The ancient magic, beliefs, rituals, offerings and lore survived to the present day, revealed by different expressions of each region in Mexico.

(TO BE CONTINUED)

Celebraciones de Octubre y los inicios del Día de Muertos

por Monica Sauza

En México, sin importar a dónde se mire y qué mes del año es, siempre hay eventos y celebraciones a través del país. Cada año, del primer día viernes de Octubre hasta el primer lunes en Noviembre, el festival con duración de un mes en Guadalajara se lleva a cabo alrededor de un tema específico; el lema de este año es “47 años de tradición.

Este popular acontecimiento en el estado de Jalisco cuenta con la presencia de artistas, bailes, películas, ballet, obras de arte, el tradicional palenque, conciertos, peleas de gallos, feria ganadera, actividades deportivas, y la venta de productos artesanales e industriales.

Del 3 al 21 de Octubre en Guanajuato, cuna de la Guerra de Independencia Mexicana y considerado por la UNESCO como Patrimonio Mundial, uno de los cuatro eventos artísticos y culturales más importantes de su tipo en el mundo, se lleva a cabo: el Festival Internacional Cervantino.

Como miembro de la Asociación de Festivales Europeos y celebrando la 40ª edición con más de 3000 artistas, esta ciudad colonial, sus plazas, parques, teatros y calles se ven colmadas con las expresiones más relevantes en ópera, teatro, danza, arte visual, música, cine y literatura proveniente de los cinco continentes. Uno puede ser parte de la algarabía en las tradicionales callejoneadas, mientras que entre risas y la música alegre de las estudiantinas,http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sGusdEygjZ4, camina por las calles empedradas descubriendo muchos secretos de las calles de Guanajuato, tal como el famoso Callejón del Beso, lo suficientemente estrecho que permitía a los amantes besarse de un balcón a otro. Este Festival tiene sus raíces en la ejecución de pequeñas obras con un tinte de comedia, los Entremeses, escritos por Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, el reconocido autor de un famoso libro que comienza con las palabras “En un lugar de La Mancha, de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme, no ha mucho tiempo que vivía un hidalgo…”, el inmortal Don Quijote. A Cervantes se le considera uno de los principales representantes del idioma español, compartiendo con William Shakespeare un sitio de honor en la literatura universal. Cervantes y Shakespeare nunca se conocieron pero, curiosamente, fallecieron el mismo año.

En México, las celebraciones reflejan el rico legado prehispánico, la cultura y la diversidad así como la influencia religiosa del colonialismo español. Tal es el caso en Yucatán con la fiesta al Cristo Exaltado del 18 al 28 de Octubre, cuando la imagen más venerada es llevada en una procesión por los peregrinos de Sitilpech hasta Izamal, donde se colocan velas y flores al pie de la imagen. El segundo día lunes durante el mes de Octubre, en el pintoresco pueblo de Santa Maria del Tule en Oaxaca, se lleva a cabo una celebración alrededor de uno de los árboles más antiguos en el mundo: el viejo Árbol de Tule o Ahuehuete (“viejo del agua” en náhuatl) de 41 metros de altura y más de 2000 de antigüedad In http://www.mexicomaxico.org/Tule/Galeria/TuleH.jpg Dos leyendas mixtecas hablan de los orígenes del Arbol de Tule (“el árbol de la iluminación”); una nos dice que el árbol fue plantado hace aproximadamente 1400 años por Ehécatl, dios del viento; la segunda habla del poderoso rey Condoy, constructor de la ciudad de Milta, quien se sentó a descansar y al clavar su bastón en el suelo, la planta brotó.

Durante la época colonial, para conservar sus valores religiosos, las comunidades indígenas adaptaron la nueva religión dentro de sus creencias ancestrales las cuales resultaron en fusiones muy particulares. Una de estas adaptaciones puede observarse en la celebración del 4 de Octubre a San Francisco de Asís en Cuetzalan, Puebla, donde el pueblo se engalana con muchos bailes espectaculares, y el Baile de los Quetzales es el más representativo. Este baile ritual prehispánico era dedicado al sol, y los danzantes aún portan grandes penachos circulares y coloridos, los cuetzaltique, que emulan los colores del pájaro quetzal.

La representación más colorida, mágica e histórica de la cultura mexicana durante Octubre-Noviembre se encuentra expresada en la tradición milenaria del Día de los Muertos. A pesar de los esfuerzos de los misioneros franciscanos quienes modificaron la fecha original de la celebración, la cual a su vez deriva de las tradiciones celtas, los antiguos rituales a los muertos sobrevivieron fuertemente arraigadas. Estos rituales también se encontraban estrechamente ligados con el final del ciclo agrícola. Las culturas prehispánicas no temían a la muerte pues creían que la muerte y la vida eran parte de un ciclo interminable que debida aceptarse como una sucesión natural del universo. A pesar de que la religión traída por los españoles en el siglo XV implanto el miedo a la muerte, la visión de los antiguos hacia la muerte era tan fuerte que prevaleció. En todas las culturas del México antiguo, la muerte tenía un sitio muy especial; un lugar adonde llegaban todas las almas inmortales. Los nahuas y mexicas llamaban a este sitio Mictlán. Sin embargo, no todos los muertos eran iguales.

Muchos se convertían en dioses; los guerreros se convertían en aves con plumajes maravillosos, cuya misión era acompañar todos los días al sol, Tonatiuh; y las mujeres que fallecían en el parto llegaban a Omeyocan, el paraíso del Sol. Sin embargo, el viaje a Mictlán no era sencillo pues los muertos debían cruzar un rio muy profundo, luchar contra bestias salvajes, etc. Por ello eran enterrados con un cuchillo de obsidiana, suficiente alimento y bebida para el viaje, y un perro como acompañante; y en el caso de un personaje importante, también éste era enterrado con sus sirvientes. Los mayas consideraban que el alma era indestructible, invisible y eterna, y la muerte era una continuación cíclica entre la vida y la muerte. Los muertos viajaban al inframundo, Xibalbá, y eran enterrados con maíz, alimentos, bebida, bienes personales y, también, un perro.

La antigua magia, creencias, rituales, ofendas y costumbres han sobrevivido hasta el presente, reflejándose a través de las diferentes expresiones de cada región en México.

(CONTINUARÁ)

______________________________

Una ex yanqui de Connecticut quien llama hogar a Cozumel desde hace más de 15 años. Laura escapó al Caribe hace años, desplazándose de una isla a otra dando clases de BUCEO. Se dedicó a perder el tiempo en Jamaica y finalmente se detuvo en Cozumel para pasar unas vacaciones de 2 semanas que aún no terminan. Convenciendo a sus padres que pagaran una elegante universidad privada, obtuvo su título en Periodismo y Laura crea semanalmente Cozumel 4You, medios sociales y artículos promocionales sobre la Isla y también es moderadora en el grupo Cozumel 4 You en Facebook que actualmente cuenta con 25,000 miembros. Fabián, s umuy tolerante marido, desde hace mucho tiempo se resignó a no tener vida privada, pues se ha visto implicado en los diversos proyectos y planes que urde Laura. Son orgullosos padres de diversos perros y gatos rescatados. Mientras contempla su paso a través de la vida en el Caribe mexicano,Laura continúa siendo la pesadilla en la existencia de su muy tradicional suegra mexicana.

- Mexico New Coins - April 18, 2025

- Feria Cedral 2025 - April 18, 2025

- 2025 Turtle Season - April 18, 2025

An ex-Connecticut Yankee who has called Cozumel home for over 18 years, Laura ran away to the Caribbean years ago, bumped around the islands teaching SCUBA diving, lost some time in Jamaica, and finally stopped in Cozumel for a 2 week vacation that hasn’t ended yet. With a degree in Journalism from a fancy private college she convinced her parents to pay for, Laura writes, edits, and creates the weekly Cozumel 4 You news, social media, and promotional articles about the island, as well as moderates the Cozumel 4 You Facebook group, which currently has over 25,000 members. Her long suffering husband, Fabian, has long since resigned himself to having zero private life, as he’s been involved in her various schemes and plots since his arrival. Proud parents to a variety of rescue dogs and cats, Laura continues to be the bane of her traditional Mexican mother-in-law’s existence, as she muses her way through life in the Mexican Caribbean. ______________________________ Una ex yanqui de Connecticut quien llama hogar a Cozumel desde hace más de 15 años. Laura escapó al Caribe hace años, desplazándose de una isla a otra dando clases de BUCEO. Se dedicó a perder el tiempo en Jamaica y finalmente se detuvo en Cozumel para pasar unas vacaciones de 2 semanas que aún no terminan. Convenciendo a sus padres que pagaran una elegante universidad privada, obtuvo su título en Periodismo y Laura crea semanalmente Cozumel 4You, medios sociales y artículos promocionales sobre la Isla y también es moderadora en el grupo Cozumel 4 You en Facebook que actualmente cuenta con 25,000 miembros. Fabián, s umuy tolerante marido, desde hace mucho tiempo se resignó a no tener vida privada, pues se ha visto implicado en los diversos proyectos y planes que urde Laura. Son orgullosos padres de diversos perros y gatos rescatados. Mientras contempla su paso a través de la vida en el Caribe mexicano, Laura continúa siendo la pesadilla en la existencia de su muy tradicional suegra mexicana.

mayan crossing May

mayan crossing May Sacred Mayan Crossing Planned for May 26 & 27...

Cancun Airport Arrival Easier

Cancun Airport Arrival Easier Cancun Immigration Announces Improvements: Free Wi-Fi &...

Cozumel Mein Schiff Cruise Ship

Cozumel Mein Schiff Cruise Ship Cozumel welcomes Mein Schiff for her...

Cozumel Cruise Ships Schedule

Cozumel Cruise Ships Schedule 31 Cruise Ships Call into Cozumel: Lower Numbers...

Leave a comment