Mexican Women History Antonia Nava de Catalán

Mexican Women History Antonia Nava de Catalán

Mexican women who made history

-

Text & Translation by Monica Sauza

Mexican women who made history:

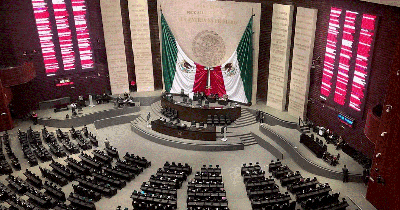

We close this historical retrospect of Women in the Mexican Independence with two other distinguished heroines whose names, along Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez and Leona Vicario, are inscribed in golden letters on a wall at the seat of the Mexican Congress of the Union (Note: Only the names of 7 women appear on that wall) and sadly there are no images or drawings of either of today’s heroines only made up portraits.

Antonia Nava de Catalán, La Generala. Resilience, endurance and courage

Although she is barely spoken of, this very courageous and brave heroine was born in Tixtla, State of Guerrero in 1779. Soldiers gave her the moniker La Generala because she always kept her husband company. Nicolás Catalán was a soldier who over time became a brigadier general in the insurgent army and commander of the State of Guerrero. The couple had eight children; five boys and three girls. They lived in Jaleaca (nowadays Jaleaca de Catalan in honor of Antonia).

The war of Independence reached Jaleaca in 1810 and the couple joined the ranks of Generalissimo José María Morelos y Pavón, and always marched at the front of the retinue. Here’s where we must pause and clarify that women were not allowed to fight; they could come along, cook, wash clothes and be nurses when needed. So, while the war was being waged to recover Tixtla, Antonia received the news that one of her sons had died in battle. Morelos wanted to comfort her, but her answer was: “…he died fulfilling his duty as a Mexican; here I present to you the four sons I have left. Three will be able to put out the fire of the enemy and the other, because he is still a child, should be given a drum with which he will roll the triumph of our cause.”

During the resistance, the insurgents recovered several strongholds from the realists but lost one in battle. The insurgents fortified in Cerro del Campo; a difficult place to access but safe for defense. After a 50-day siege, and relentless fighting, the troops were discouraged, distressed and starving. The general agreed to kill one soldier for every ten men to serve as food for the troops. Along with two other ladies, with great determination Antonia confronted General Bravo and said: “We come because we have found a way to be useful to our country. We cannot fight, but we can serve as food!. Take our bodies to be distributed as rations to the soldiers.” She held a dagger to her chest but was stopped by a soldier. Her words encouraged and revived the spirit of the troops, and full of courage she exclaimed: “It’s eleven o’clock this night; the enemies are sleeping. Give us weapons and together let us smash the siege.” The women armed themselves with machetes and bludgeons and went out to fight the enemy.

After winning this episode, and others yet to come, Antonia was the only woman who was allowed to ride her horse triumphantly, next to her husband, into Mexico City along the insurgent army in 1821 when the Mexican Independence was declared. The couple lost 3 children to the war and after all their feats returned to Chilpancingo, Guerrero, where Antonia died at the age of 63 in 1843.

Mariana Rodríguez del Toro de Lazarín, the Conspiracy of 1811

In the social revolution which brought about the independence of Mexico from the Spanish domination and began in 1810, culminating in 1821, Mariana Rodriguez del Toro de Lazarín’s appears as a heroine whose exemplary role and encouragement led many to join de cause.

Attires and life in Mexico in the 19th century; National Museum of Art of Mexico

Vetimenta y la vida en México en el siglo XIX; Museo Nacional de Arte de MéxicoBorn in 1778 (some say in the 1790s) to a wealthy family in the colonial city of Querétaro, Mariana and her family always wanted to see Mexico free from the Spanish rule, hence they eagerly financed the insurgent cause. Her studies in philosophy shaped her liberal and revolutionary ideas. She married Manuel Lazarín, co-owner of an important mine. Due to their social standing, the Lazarín household was no stranger to parties and gatherings as a front for the advocates of an independence.

One night in 1811, while in one of these gatherings the bells of the churches in town tolled incessantly. The Lazaríns and their guests were startled as they assumed the bells rung proclaiming the victory of the uprising. However, a visitor who came in late to the gathering informed that Miguel Hidalgo, the main generals and twelve hundred people had been arrested by the realists. Everyone was dismayed at the defeat, but Mariana stood up outraged and is known to have said: “What is going on, gentlemen? Are there no men in America apart from the generals who have fallen prisoners? Let us free the prisoners; seize the viceroy and hang him!” We must remember that women of Mariana’s social class could only be wives or nuns, this was a very audacious challenge to the men of her time. She was key in the creation of the “Conspiracy of 1811” as not only did she encourage many men and people in general, to keep fighting but concocted the plans to kidnap the viceroy and negotiate the freedom of the insurgents. Many conspirators walked by her side, but one, on the verge of death, gave the Lazaríns up. Both were imprisoned. She would have been shot had she not been “ill with pregnancy”. Even in prison, she persuaded others to join the cause. She was released in 1820 and died in 1821, the year the Independence was declared.

Mexicanas que hicieron historia

Texto & traducción de Monica Sauza

Mexicanas que hicieron historia:

Cerramos esta retrospección histórica de las Mujeres en la Independencia de México con otras dos ilustres heroínas cuyos nombres, junto con el de Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez y el de Leona Vicario, están inscritos en letras doradas en un muro de la sede del Congreso de la Unión en México (Nota: En este muro sólo aparecen los nombres de 7 mujeres), y lamentablemente no existen imágenes ni ilustraciones de ninguna de las dos heroínas, sólo retratos ficticios.

Antonia Nava de Catalán, La Generala. Resistencia, entereza y valor

A pesar de que casi no se habla de ella, esta valiente y aguerrida heroína nació en Tixtla, Estado de Guerrero, en 1779. Los soldados le dieron el apodo de La Generala pues siempre estaba en compañía de su esposo. Nicolás Catalán fue un soldado que con el tiempo llegó al rango de general de brigada del ejército insurgente y luego comandante del Estado de Guerrero. El matrimonio procreó 8 hijos: cinco varones y tres mujeres. Vivieron en Jaleaca (Hoy Jaleaca de Catalán en honor a Antonia).

La guerra de independencia llegó a Jaleaca en 1810 y la pareja se unió a las filas del Generalísimo José María Morelos y Pavón, y siempre marcharon al frente de la compañía. Aquí es a donde es necesario hacer una pausa para aclarar que a las mujeres no se les permitía pelear; podían acompañar, cocinar, lavar ropa y hacerla de enfermeras cuando fuera necesario. Mientras se libraba guerra para recuperar Tixtla, Antonia recibió la noticia de que uno de sus hijos había fallecido en batalla. Morelos quiso consolarla pero su respuesta fue: “…murió cumpliendo con su deber de mexicano; aquí le presento a los cuatro hijos que me quedan. Tres podrán apagar el fuego del enemigo y el otro, por ser todavía un niño, hay que darle un tambor con el cual redoble el triunfo de nuestra causa”.

Durante la resistencia, los insurgentes recuperaron varios bastiones de manos de los realistas, pero perdieron uno en la batalla. Los insurgentes se fortificaron en el Cerro del Campo; un lugar de difícil acceso pero seguro para la defensa. Tras 50 días de asedio y combates sin tregua, las tropas se estaban desanimadas, angustiadas y hambrientas. El general acordó matar a un soldado por cada diez hombres para que sirviera de alimento a las tropas. Junto con otras dos damas, Antonia enfrentó al general Bravo con gran determinación diciendo: “Venimos porque hemos hallado forma de ser útiles a nuestra patria. ¡No podemos pelear, pero podemos servir de alimento!”. Se llevó un puñal al pecho pero un soldado la detuvo. Sus palabras infundieron ánimos y reanimaron el espíritu de las tropas, y llena de valor exclamó: “Son las once de la noche; los enemigos duermen. Dennos armas y juntos rompamos el asedio”. Se armaron las mujeres de machetes y garrotes y salieron a pelear contra el enemigo.

Después de ganar este episodio, y otros aún por venir, Antonia fue la única mujer a la que se le permitió entrar triunfante a la Ciudad de México cabalgando al lado de su marido, junto al ejército insurgente en 1821 cuando se declaró la Independencia de México. La pareja perdió 3 hijos en la guerra, y después de todas sus hazañas regresaron a Chilpancingo, Guerrero, donde Antonia falleció a la edad de 63 años en 1843.

Mariana Rodríguez del Toro de Lazarín, la Conspiración de 1811

En la revolución social que propició la independencia de México de la dominación española, y que inicio en 1810 culminando en 19821, Mariana Rodríguez del Toro de Lazarín aparece como una heroína cuyo papel ejemplar y ánimo llevo a muchos a unirse a la causa.

Mexican Congress of the Union

Congreso de la UniónNacida en 1778 (algunos dicen que en la década de 1790) en el seno de una familia acomodada en la ciudad colonial de Querétaro, Mariana y su familia siempre quisieron ver un México libre del régimen español, de ahí que financiaran con entusiasmo la causa insurgente. Sus estudios en filosofía forjaron sus ideas liberales y revolucionarias. Contrajo matrimonio con Manuel Lazarín, copropietario de una importante mina. Debido a su posición social, el hogar de los Lazarín no era ajeno a fiestas y reuniones que servían de fachada a los partidarios de una independencia.

Una noche de 1811, durante una de estas reuniones repicaron las campanas de la ciudad sin cesar. Los Lazarin y sus invitados se sobresaltaron al suponer que las campanas sonaban proclamando la victoria del levantamiento. Sin embargo, un visitante que llegó tarde a la reunión informó que Miguel Hidalgo, los principales generales y mil doscientas personas habían sido detenidos por los realistas. Todos estaban consternados por la derrota, pero Mariana se levantó indignada y se sabe que estas fueron sus palabras: “¿Qué sucede señores? ¿No hay hombres en América aparte de los generales que han caído prisioneros? ¡Liberemos a los prisioneros, tomemos al virrey y ahorquémoslo!”. Debemos recordar que las mujeres de la clase social de Mariana sólo podían ser esposas o monjas; este era un desafío muy audaz a los hombres de su época. Fue clave en la creación de la “Conspiración de 1811! Ya que no sólo animó a muchos hombres y al pueblo en general, a seguir luchando, sino que urdió los planes para secuestrar al virrey y negociar la liberación de los insurgentes. Muchos conspiradores caminaros a su lado, pero uno, estando a punto de morir, delató a los Lazarín. Ambos fueron encarcelados. Ella habría sido fusilada de no haber estado “enferma de embarazo”. Incluso estando en prisión, persuadió a otros para que se unieran a la causa. Fue liberada en 1820 y falleció en 1821, el año en que se declaró la independencia.

Translator & Author at Cozumel 4 YouAnother escapee from Mexico City, Monica hasmade Cozumel her definite home.Since her arrival -in 981- she worked in tourism in all the usual venues:hotels, scuba diving, airport, ferries, until the opportunity to practice in her chosen field grew.Since the latter part of the 70s Monica has been translating and interpreting, fully devoting herself to it since 1998, and has assisted foreigners and Island residents establish residence and businesses- She is a Translator with extensive experience, an avid historian and a great source of local lore and legends.

Otra fugitiva de la Ciudad de México. Mónica ha hecho de Cozumel su hogar definitivo. Desde su llegada en 1981, trabajo en turismo en todos los lugares habituales: hoteles, buceo, aeropuerto, ferries, hasta que se abrió la oportunidad de desempeñarse en su campo. Desde finales de la década de los años 70 Mónica ha estado traduciendo e interpretando, dedicándose plenamente a ello a partir de 1998, y ha asistido a extranjeros y locales de la Isla a establecer su residencia y sus negocios. Es traductora con gran experiencia, ávida historiadora y una gran fuente de tradiciones y leyendas locales.Latest posts by Monica Sauza (see all)- Mexican Women Rowing History - February 13, 2026

- Tamales February 2 - February 6, 2026

- $10 and $20 peso coins coming into circulation in 2026 - January 30, 2026

Another escapee from Mexico City, Monica has made Cozumel her definite home. Since her arrival -in 981- she worked in tourism in all the usual venues: hotels, scuba diving, airport, ferries, until the opportunity to practice in her chosen field grew. Since the latter part of the 70s Monica has been translating and interpreting, fully devoting herself to it since 1998, and has assisted foreigners and Island residents establish residence and businesses- She is a Translator with extensive experience, an avid historian and a great source of local lore and legends. Otra fugitiva de la Ciudad de México. Mónica ha hecho de Cozumel su hogar definitivo. Desde su llegada en 1981, trabajo en turismo en todos los lugares habituales: hoteles, buceo, aeropuerto, ferries, hasta que se abrió la oportunidad de desempeñarse en su campo. Desde finales de la década de los años 70 Mónica ha estado traduciendo e interpretando, dedicándose plenamente a ello a partir de 1998, y ha asistido a extranjeros y locales de la Isla a establecer su residencia y sus negocios. Es traductora con gran experiencia, ávida historiadora y una gran fuente de tradiciones y leyendas locales.

Cozumel Carriage Horses

Cozumel’s Carriage Horses Get a Deadline—and a Much-Needed Break For years, they’ve...

ByMonica SauzaSeptember 27, 2024Cozumel Cruise Ship Arrivals 2025

Cozumel Cruise Ship Arrivals 2025: A Banner Year Cozumel had a banner...

ByMonica SauzaSeptember 27, 2024San Miguel Cozumel Celebrates 176 Years

Cozumel, Q.Roo — On November 21, San Miguel de Cozumel celebrated its...

ByMonica SauzaSeptember 27, 2024Cozumel Sailing

How We Came to Call Cozumel Home: Dan Libbert, owner of Cozumel...

ByMonica SauzaSeptember 27, 2024

Leave a comment